Introduction

A Romeo spy is a male spy who seduces women to get them to reveal secrets. The term was coined by Markus Wolf, the former head of East Germany's foreign intelligence service the Stasi. Sexpionage [4].

Former Assistant FBI Director William C. Sullivan in testimony before the Church Committee on 1 November 1975 stated: “The use of sex is a common practice among intelligence services all over the world. This is a tough dirty business. We have used that technique against the Soviets. They have used it against us” [4].

Countries never talk about their own sexpionage, always the enemies’, just like they do for Manchurian candidates and mind controlled assassins. “Intel agencies” use Romeo spies against foreign countries but also against their own citizens, as evidenced when the London Met Police targeted women in environmental protests for relationships and spying, see Spycops [5]. The honeypot is ubiquitous, as the world runs by blackmail, see Blackmail, Child Abuse [160].

Mind Controlled NWO Army Sleepers Activation

Various people have reported that mind controlled sleepers are being activated for the NWO army, Laura Worley being one who has said this. Obviously it is best to deprogramme if you know you have been mind controlled, there is some help here - NWO Army Programming Self Help 2 [12]. At least two people have received morse code signals within the last few weeks, which they think may be connected to back alters delta activations, they hope not obviously.

There are millions of mind controlled people, see How many mind controlled slaves are there? [14]. Their jobs will be many and various not just the well known Manchurian candidate role, which is described in the next section. Many may well feature delta alters, and I suspect that many security people and the migrants from the weaponised migration are activated, awaiting activation or further activation. A proportion of the mind controlled will be activated as beta kittens, sex and blackmail slaves and a proportion will be activated as Romeo Spies.

Some awakened sleepers may have already recently infiltrated their targets. Watch out for delta trained individuals infiltrating survivors. Their brief may well be to cause chaos and division, especially amongst groups of survivors. They will be pointed towards where they can cause most damage. Their background may be convincing but they may have been repurposed by the cabal. A romeo white knight promising the earth for survivors, that they have the only solution, but they are riding a trojan horse for the cabal, perhaps to round up survivors information. Take care.

Manchurian Candidate

Manchurian Candidate was a 1959 book by Richard Conlon, later made into films in 1962 and 2004. This maybe many people’s only knowledge of mind control. The full 1962 video is available on this link, and worth a watch as an introduction to the whole concept of mind controlled sleepers assassins.

Odysee Manchurian Candidate Full video 2 hours [1c] or other [1]

The following is a one hour “documentary” about it.

Odysee CIA – MK Ultra – Manchurian Candidates – Controlled Assassins [11c]

For more see Manchurian Candidates – MK Ultra Mind Control Assassins [175].

Britain’s Met Police Detective became Russia’s Romeo Spy

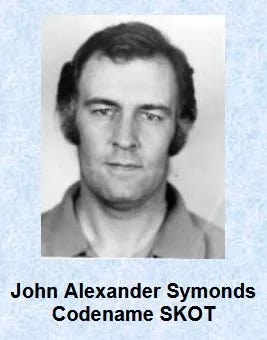

Detective Sergeant John Symonds was one of the London Metropolitan Police caught up in the “Times Inquiry of 1969” about police corruption.

He is probably most famous for his quote which he gives as “Don’t forget always to let me know straight away if you need anything because I know people everywhere, because I am in a little firm in a firm, alright?”. This was caught on tape and became synonymous with police corruption and freemasonry.

Symonds was a minor player in corruption compared to many others and he was perhaps unlucky as there was routine low level corruption in the Met at the time, and he was made scapegoat for other officers much worse higher level corruption. Met Police corruption was integral to child sexual abuse scandals in London.

British ex Detective Sergeant John Symonds became a Romeo Spy working for the Russians. Here is a pdf of John Symond’s book. It’s an interesting read and shows a side that you not normally see or hear about, funny but deadly serious.

Romeo Spy by John Alexander Symonds pdf

This was my original blog from 2016 foxblog1 John Symonds and his Book Romeo Spy [3].

Transcript text follows after the links, for those who want to read it in this post.

Links

[1] Romeo Spy website http://www.romeospy.co.uk/

[1a] Romeo Spy download http://www.cryptome.org/0002/romeo-spy.doc

[2] 2018 Jun 4 Archive CIA Romeo Spies https://web.archive.org/web/20240228213443/https://www.cia.gov/stories/story/romeo-spies/

[3] 2016 Apr 16 foxblog1 John Symonds and his Book Romeo Spy https://cathyfox.wordpress.com/2016/04/16/john-symonds-and-his-book-romeo-spy/ #JohnSymonds #RomeoSpy

[4] wikipedia Sexpionage https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sexpionage

[5] Spycops https://www.spycops.co.uk/

[6] 2024 May 11 Mail The masters of SEXPIONAGE: Glamorous female spies who used sex to lure male targets - from Russian who now teaches women how to get any man they want to the US agent who 'used a bedroom like Bond used a Beretta' https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-13392371/sexpionage-glamorous-female-spies-sex-male-targets-Russian-agent-bedroom-Bond.html

[7] Sexpionage: The true story of the Romeo spies

[8] The Spy Who Loved Me: When East German Spies Broke Hearts In The Cold War | Sexpionage | Timeline https://odysee.com/@FoxesAmazingChannel:8/The-Spy-Who-Loved-Me_-When-East-German-Spies-Broke-Hearts-In-The-Cold-War-_-Sexpionage-_-Timeline-4G2qqI8k3do-720p-1715513578:8

21 Jul 2017 Sexpionage tells the stories of two women who were seduced by secret agents working for the East German intelligence service, the Stasi. At the height of the Cold War the Stasi would regularly despatch their agents to the West German capital, Bonn, armed with the task of forming long term relationships with single women working at embassies or government ministries. These women were unwittingly tapped for top secret information which was then passed on to the East. Both Gabriele Kliem and Margaret Hike had no idea that their lovers were spies until both women were arrested for treason. This film tells the story of the years they spent with their secret agent lovers and explores the feelings they are left with after the most significant relationships of their lives were revealed to be a sham.

[9] Guardian The spy who loved her https://www.theguardian.com/education/2004/nov/18/artsandhumanities.highereducation

[10] Ya Basta The Spy Who Loved Me: When East German Spies Broke Hearts In The Cold War https://yabasta1.wordpress.com/2024/05/12/the-spy-who-loved-me-when-east-german-spies-broke-hearts-in-the-cold-war/

[175] 2020 May 29 foxblog1 Manchurian Candidates – MK Ultra Mind Control Assassins https://cathyfox.wordpress.com/2020/05/29/manchurian-candidates-mk-ultra-mind-control-assassins/

[12] 2023 Nov 19 substack foxblog3 NWO Army Programming Self Help 2 https://foxyfox.substack.com/p/nwo-army-programming-self-help-2 #nwoarmy #programming #nwo #mindcontrol #DrFauci

[14] 2023 Jul 23 Foxblog3 How many mind controlled slaves are there? https://foxyfox.substack.com/p/how-many-mind-controlled-slaves-are #mkultra #mindcontrol #mindcontrolledslaves

[160] 2020 Sept 4 cathyfoxblog Blackmail, Child Abuse https://cathyfox.wordpress.com/2020/09/04/blackmail-child-sexual-abuse-and-q/ (high level csa)

Transcript Romeo Spy by John Symonds

Contents

Abbreviations

Introduction by Nigel West

I Encounter in Morocco

II Bulgaria

III Moscow

IV India

V Australia

VI London

VII Mitrokhin

VIII HOLA

Abbreviations

ACC Assistant Commissioner, Crime

ASIO Australian Security Intelligence Organization

BfV Federal German Security Service

BND Federal German Intelligence Service

BOSS South African Bureau of State Security

CIA Central Intelligence Agency

CID Criminal Investigation Division

CPGB Communis Party of Great Britain

DAC Deputy Assistant Commissioner

DCI Detective Chief Inspector

DCS Detective Chief Superintendent

DI Detective Inspector

DPP Director of Public Prosecutions

DS Detective Sergeant

FCD First Chief Directorate

FRG Federal Republic of German

GCHQ Government Communications Headquarters

GDR German Democratic Republic

GRU Soviet Military Intelligence Service

HVA East German Intelligence Service

JIC Joint Intelligence Committee

KDS Bulgarian Security Service

KGB Soviet Intelligence Service

MI5 British Security Service

NKVD Soviet Intelligence Service

NSA American National Security Agency

OPS Obscene Publications Squad

PUS Permanent Under-Secretary

REME Royal Electrical & Mechanical Engineers

SCD Second Chief Directorate

SHAPE Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe

SIS British Secret Intelligence Service

StB Czech Intelligence Service

SVR Russian Federation Intelligence Service

YCL Young Communist League

Introduction

In the middle of March 1992 an elderly, shabbily-dressed Russian carrying a battered suitcase walked into the British Embassy in the Latvian capital of Riga and asked to see a member of the British Secret Intelligence Service. He was insistent, and eventually he was shown into an interview room, usually used by visa applicants, where he was spoken to by a young woman who was to serve him with a cup of tea, and transform her career over the next few minutes. The woman did not introduce herself as a diplomat, and was actually the embassy’s secretary. Although the man wanted to speak to an intelligence officer, there was no SIS officer, and no local station commander. That station might have consisted of an officer and an SIS secretary, two intelligence professionals at the front line during the collapse of the Soviet Bloc, representing a clandestine organisation, headed at its headquarters in London by Sir Colin McColl, but SIS had not been operational in the newly independent republics of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia since before the Second World War. The British embassy was accommodated in the International Trade Centre, a building that had previously housed the Communist Party’s central committee, and the staff consisted of the Russian-speaking ambassador, Christopher Samuel, his first secretary, Mike Bates, one secretary, and Steve and Margaret Mitchell, a husband and wife team from the Stockholm embassy who acted as the embassy’s secretary and the archivist. The embassy had been opened the previous October, when it had consisted of Samuel’s hotel room, a satellite phone, a bag of money under his bed and a Union Jack on his door. In a similar, simultaneous exercise, Michael Peat had been sent to Vilnius and Bob Low to Tallin.

The elderly Russian, who had arrived on the overnight train from Moscow, spoke no English, but explained that his name was Major Vasili Mitrokhin, formerly of the KGB. He said he was aged sixty-nine, and had joined the KGB in 1948. Reaching into his bag, under a pile of what appeared to be dirty laundry and the remains of several meals, he removed a removed a pair of school exercise books. Inside, written in neat Cyrillic script, was a sample of what was to become one of the greatest intelligence coups of the era. Although this strange offering had failed to impress the CIA Chief of Station across town at the American Embassy, the person Mitrokhin took to be his British counterpart was astounded, not just by the content, but by her visitor’s extraordinary tale. He claimed that from late 1956 until his retirement in 1984 he had been in charge of the KGB’s archives at the First Chief Directorate’s headquarters at Yasenevo, on the Moscow ring road. For the previous twenty-five years, since the premature conclusion of his only overseas assignment, to Israel, he had supervised the tens of thousands of files that had been accumulated by the world’s largest and most feared intelligence agency, and had taken the opportunity to read many of the most interesting ones. Astonishingly, he had spent twelve of those years, and much of his retirement, reconstructing his own version of what he regarded as the most significant dossiers, documenting Stalin’s crimes, Khrushchev’s follies, Brezhnev’s blunders and the many misdeeds committed in the name of Soviet Communism. For most of his career, he said, he had been disenchanted with the Soviet system, had listened to western radio broadcasts and read dissident literature. In 1972, when he was made responsible for checking the First Chief Directorate files being transferred from the old headquarters in the Lubyanka, to the KGB’s modern building on the outskirts of Moscow, he embarked on what amounted to the construction of an illicit history of the Soviet Union’s most secret operations.

Could the material be genuine? Was this strange, shambling figure a Walter Mitty fantasist? Why had he been turned away by the CIA? Would it have been possible for the KGB’s security to have been breached in such an amateurish way? Mitrokhin asserted that he had simply copied the original files and walked out of the heavily-guarded KGB compound with his hand-written notes stuffed into his socks. He had then rewritten a detailed account of the files from his scraps of paper into exercise books and other convenient binders which he had hidden in a milk churn concealed under his country dacha. In return for political asylum for himself and his family he was willing to offer his entire collection, amounting to a full six cases of documents. Furthermore, he was willing to collaborate with SIS so the material could be properly interpreted and eventually published, and he promised to return on 9 April with more samples of his handiwork. On that date he was met by a delegation of SIS officers who examined some two thousand sheets of his archive and scrutinized his Party membership card and his KGB retirement certificate. Acknowledging the authenticity of what he had shown them, a further appointment was made two months’ hence to meet the man now codenamed GUNNER by SIS, and on 11 June he returned to Riga carrying a rucksack containing yet more material.

GUNNER’s documents looked sensational, but why had he been rejected by the CIA? This remains something of a mystery, if not an embarrassment at the CIA’s headquarters, but the then chief of the Soviet/Eastern Europe Division, Milton Bearden, has acknowledged that he was besieged with offers from potential defectors in the months following the Soviet collapse, and as each authentic source was receiving an average of a million dollars, and he was receiving one worthwhile offer every forty days, the Directorate of Operations was simply running out of money and failed to take the shambling old man sufficiently seriously. Bearden had been assigned to language training in preparation for his appointment as Chief of Station in Bonn, with John MacGaffin as his replacement, and Tom Twetton had just become Deputy Director for Operations. Somehow, in the confusion at Langley and maybe a screw-up in Riga where Ints Silins was the US Ambassador, Mitrokhin had been rejected. Whatever the excuse, Paul Redmond, the CIA’s chief of counter-intelligence, was later to agree that the CIA had missed a golden opportunity, leaving him to SIS’s tender mercies.

Mitrokhin was to undergo further interviews in England early in September 1992, when he spent almost a month in the country under SIS’s protection, staying at safe-houses. When he returned to Moscow on 13 October he did so for the last time and less than a month later, on 7 November, he accompanied his family to Latvia and was issued with British passports enabling them to fly to London.

The details of how Mitrokhin subsequently made a second journey to Riga, accompanied by his wife and son, remain classified, as do the circumstances in which an SIS officer later visited his empty dacha outside Moscow and recovered his secret hoard of papers and carried them undetected to the local SIS station, headed by John Scarlett at the British Embassy. Now codenamed JESSANT, no official announcement was made of Mitrokhin’s defection, and in the chaos of 1992 his disappearance from the Russian capital probably went unnoticed. His existence in the archives had been a solitary existence, and he was unpopular with his colleagues, considered an awkward stickler for regulations, unwilling to speed up bureaucratic procedures when offered the customary bottle of vodka as an inducement. However, in the months that followed, numerous counter-intelligence operations were mounted across the globe, each resulting in a stunning success. Near Belfauz, Switzerland, booby-trapped caches of weapons and covert radio equipment were dug up in the forest; In Tampa, Florida, retired US Army Colonel George Trofimoff was approached by FBI special agents posing as Russian intelligence officers, to whom he admitted in a secretly videotaped meeting lasting six hours that he had spied for the Soviets for twenty-five years since his recruitment in Nuremberg in1969; In Australia a senior ASIO analyst was identified as a long-term source for the KGB, but he was not arrested; In a motel in Virginia a former National Security Agency cryptographer, codenamed DAN by the KGB, was detained and charged with espionage. No public statements were issued, but in Moscow the KGB’s successor organisation, the SVR, began to count the accumulating losses. Well-established assets in every corner of the world were being ‘wrapped-up’ in a series of operations that amounted to a colossal intelligence disaster of unprecedented proportions. George Trofimoff, codenamed ANTEY, MARKIZ and KONSUL in Mitrokhin’s files, resulted in the imprisonment of the most senior American army officer ever to be charged with espionage.

In London, Mitrokhin’s arrival and resettlement was but part of a project that was to have lasting consequences. After so many years confined to Moscow he found it hard to adapt to life in England, and to the detriment of his health he concentrated on supervising the transfer of his precious archive onto a massive computer database. As each new case was revealed, SIS despatched a suitably sanitized summary to the appropriate allied security or intelligence agency to exploit, seeking in return only an assurance that the secret source of the information should not be disclosed. On only one occasion, the prosecution of the NSA analyst Robert Lipka in 1997, was there a request that Mitrokhin travel to Philadelphia to testify in person to the origin and authenticity of his dossier, but in the end the spy’s plea of guilty to a single charge of espionage obviated the need for him to appear as a witness. Lipka was sentenced to eighteen years’ imprisonment in September 1997, completely baffled as to how the FBI had tracked him down after a gap of twenty-three years.

One of SIS’s many satisfied customers was the British Security Service, MI5, which was provided with tantalising glimpses into how the KGB had operated in Britain over more than six decades. Where mere suspicions had been marked on personal files, Mitrokhin confirmed guilt of espionage; when an MI5 investigation had been shelved for lack of progress, Mitrokhin supplied additional leads. And in the case of Melita Norwood, a life-long Communist believed to have once operated as a spy, Mitrokhin revealed that she was HOLA and had been in contact with KGB’s illegal rezident in London until January 1961. Born in London in 1912 of an immigrant Latvian bookbinder named Sirnis, Melita had been a member of the CPGB and had been linked to Percy Glading in 1938 when the former CPGB National Organiser was imprisoned for espionage. Her name, and her family’s address in Hampstead were found in a notebook owned by Glading at the time of his arrest, when he was charged with stealing secrets from the Woolwich Arsenal, but MI5 had not pursued the clue. Later she had joined the headquarters of the British Non-Ferrous Metals Association in Euston as a typist for one of its directors, G.J. Bailey, and this had given her access to nuclear secrets as the organisation was a component of the Anglo-American project to develop an atomic bomb, which the NKVD had dubbed Operation ENORMOZ. In 1964 she had been tentatively identified as the spy codenamed TINA who had been mentioned in a single VENONA message from Moscow dated 16 September 1945. According to the text transmitted to the rezident in London, ‘her documentary material on ENORMOZ is of great interest and represents a valuable contribution to the development of the work in this field’. However, the addressee, Konstantin Kukin, had been directed to ‘instruct her not to discuss her work with us with her husband and not to say anything to him about the nature of the documentary material which is being obtained by her’. Thus MI5 established in 1964, when the text was finally decrypted, that Mrs Norwood had been an active spy in September 1945, and had been ordered not to confide in her husband, a Communist school-teacher, about her espionage. Surprisingly, despite this evidence that she had engaged in betraying atomic secrets, MI5 chose not to take any action, and did not even bother to interview her, on the grounds that she had remained a hardened CPGB member and therefore was unlikely to cooperate with any interrogation.

No criminal prosecutions resulted in England as a consequence of Mitrokhin’s disclosures, but in the counter-intelligence world inhabited by molehunters and surveillance experts there are other, equally important advantages to be achieved. Most controversially, one such objective, supervised by John Scarlett, who by then had been expelled from Moscow, was to publish a historical account of Mitrokhin’s collection, and this was accomplished in September 1999 with the help of the Cambridge historian Christopher Andrew. Their joint effort, entitled The Sword and the Shield in the United States, was released amid international publicity, with much of the attention focusing on two spies particular. One was the elderly Melita Norwood, by then a grandmother living in a London suburb, and the other was SCOT, a former Scotland Yard detective, John Symonds, described as ‘the most remarkable British agent identified by Mitrokhin outside the field of S & T’. Symonds may not have had a talent for science and technology, but he possessed other skills that he had made available to the KGB for more than eight years.

The drama behind the exposure of these two masterspies is itself worthy of an entire study in itself, and MI5’s complacency was to be the source of considerable criticism when Mitrokhin’s material was made public, but MI5 had not discovered until June 1999 that a BBC journalist, David Rose, had been researching an unrelated television documentary entitled The Spying Game in which he intended to include an interview with Mrs Norwood. He filmed this secretly in August when he had called at her home in Bexleyheath, Kent, although quite how Rose learned that Melita Norwood had been a spy remains unclear, but the likelihood is that he was told about the case while he was being briefed for his film. In any event, with the certainty that Mrs Norwood was to feature In Rose’s broadcast, the decision was taken at the very last moment to insert her real name, and that of John Symonds, in the pages of The Mitrokhin Archive, thereby attracting considerable media coverage when The Times serialized the book in early September 1999.

The revelation contained in Mitrokhin’s files that John Symonds had operated as a KGB agent codenamed SCOT proved hugely embarrassing for the Security Service because the ex-policeman and army officer had long ago volunteered a confession that had been rejected as being too fanciful to be true. Having disappeared when charged with corruption in 1972, Symonds had spent the next few years working for the KGB, and when he finally returned to Britain in April 1980, having travelled across the world on various different passports, he surrendered to the authorities and was sentenced to two years’ imprisonment, having been found guilty at the Old Bailey on two charges of corruption. Although Symonds had offered MI5 a potentially vital counter-intelligence breakthrough, detailing many of the operations he had participated in under the KGB’s direction, he had been rebuffed because his story was considered too incredible to be believed. It was only after his release from Ford open prison, and Mitrokhin’s defection, that MI5 realised what an opportunity it had passed up. Far from being a dreamer and hoaxer, Symonds had been entrusted with a series of sensitive operations by his KGB controllers, and was considered in Moscow to have performed his tasks well.

Even after Mitrokhin’s confirmation of Symonds’ covert role as a KGB spy, the Security Service could not bring itself to accept his renewed, generous offer of cooperation, so doubtless the pages that follow will be read with as much interest by the molehunters of Thames House as by other readers. What led Symonds to collaborate with the KGB in the Moroccan capital of Rabat? How many western secretaries with access to classified information did he seduce while entrapping the unwary at Bulgarian beach resorts? What is the truth behind his allegations of corruption in the Metropolitan Police? Who were his targets among the unmarried women working at the British Embassy in Moscow? Why did his German girlfriend agree to betray secrets to the KGB? Did he really recommend that a Special Branch bodyguard responsible for protecting the KGB defector Oleg Lyalin could be bribed?

What follows is a story that no novelist or thriller-writer could have invented. It is the career of a disappointed soldier, an idealistic police officer, a desperate fugitive and manipulative spy. It is also the story of Nellie Genkova, a beautiful Bulgarian language teacher who remained loyal to a man she knew as John Arthur Phillips, supposedly a Communist Party official who spent much of the year travelling the world. Incredible, certainly, but also absolutely true.

Nigel West August 2010

Chapter I

Encounter in Morocco

My first encounter with the KGB required a detailed account of my background, and I took several days to prepare a document that set out my career thus far. It began with my birth in Peterborough in 1935, and ended with my hasty exit from London in 1972. In between were the events that had shaped my two unexpectedly short experiences as a police officer.

I was educated at Rougemont, a private prep school in Newport, south Wales, and then went to St Julian’s, a good grammar school where I took I joined the Boy Scouts and took an interest in the church. As someone who was later to be accused of being a professional perjurer, this may seem odd, but my scout troop met in the church hall and I had contemplated taking holy orders. I had started and edited our troop magazine, Contact, and had badgered the local mayor and the bishop into contributing articles. When the wartime air aces ‘Cats Eyes’ Cunningham and Group Captain Leonard Cheshire had visited our church I had persuaded them to submit to interviews, and when I sent them courtesy copies of the published version I was invited to attend a Christian summer camp. This consisted of plenty of bible classes and prayer meetings, and brought me into contact with the children of many senior churchmen. Eventually my preoccupation petered out, but the enthusiasm I showed for religion was typical of the way I threw myself into particular interests.

I also excelled rugby, boxing and water polo, but these were physical achievements, not signs of any academic accomplishments, so I did not complete the sixth form before I joined the army at the age of seventeen for the Officer Training Corps. This was a career choice encouraged by my father, then still a serving officer based at the Royal College of Military Science, despite lost a part of his left hand in an explosion at the Woolwich Arsenal during the Second World War while conducting secret experimental proof work. He always had good connections, and one of my godfathers was his former commanding officer, later to sponsor my application for a commission to the War Office Selection Board, while another was a senior Special Branch officer, Commander Flood, who was to give me sound advice about how to get on in the Met. My father had met Flood when the latter had been sent to investigate a mysterious explosion in 1940 which was suspected to have been an act of sabotage by Nazi spies. Flood concluded the incident had been an accidental detonation, and the two men had remained in touch with each other after the war, when he had been based at Fort Halstead.

I was posted to the British Army of the Rhine at Munster, to join my Royal Artillery regiment, as a private soldier, on being commissioned in 1953 and came to command Y (Survey) Troop, 94th Locating Regiment. Although I had volunteered for combat in Korea, I was sent on an Officer’s Gunnery Course at Larkhill in Wiltshire, where I acquired some knowledge of 25-pounders and counter-bombardment skills.

Apart from my encyclopaedic grasp of field artillery, my other lasting asset from the army was an invitation in 1956 to join the army lodge of the Freemasons. I was assured that being ‘on the square’ would help my career, and it certainly did me no harm when I later joined the police and found that the local lodge played an important part in gaining promotions. I knew the lodge exercised great influence in the military because, shortly before leaving the army I recommended that my younger, middle brother Leonard, then a lowly REME corporal, should join. Promotion to Quarter-Master followed soon afterwards, and he later received a commission and was transferred to Middle Wallop where he spent much of his career developing computer systems and avionics for helicopters of the Army Air Corps. He was to become master of his lodge, eloquent proof of the influence exercised by the Brethren.

After nearly three years in the army I was persuaded to join the Metropolitan Police in what would now be described as a fast-track with the promise of swift promotion to the rank of inspector, the objective being the creation of an officer corps within the force, a concept that had been abandoned before the war, following Lord Trenchard’s reforms which had created the training school at Hendon. There were about two dozen of us, all from a similar background, who had been approached to help transform the Met into a professional organisation based on military lines, and I recall particularly an ex-Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm pilot, and another army officer, who held views similar to mine. Within a year we had all left the police in disgust, most appalled by the standards of discipline and the pervasive culture of mild corruption. My first encounter with the Met’s hidden management occurred when Hendon’s Commandant invited me to a meeting which was attended exclusively by Freemans. As well as the Commandant, who was later to be appointed Chief of the City of London force, there were some elderly members of the permanent staff, and a group of the cadets. It was here that I learned of the flying start enjoyed by those of us ‘on the square’ who would be joining one of the many police lodges. We would have advance access to exam papers, the names of contacts to help with interviews and numerous other advantages. No wonder so many inappropriate accelerated promotions occur in the police, and no wonder there is such resentment among those who have seen how the Brethren help each other.

Another good example was my arrest while on the ‘Queer Patrol’ in the Covent Garden urinals, of Tom Driberg, the Labour MP whom I had caught engaged in buggery with another man. A notorious, predatory homosexual, I marched him off to Bow Street, having angrily rejected his offer of £5 to forget the matter, but soon afterwards he had telephoned another Labour MP, and future prime minister, who arrived at the police station and demanded to see Chief Superintendent ‘Bones’ Jones who lived in quarters directly over the station. Obviously this was not a total surprise to some officers, and all involved seemed confident of the procedure. Soon afterwards both MPs left the building in high spirits, my pocketbook was confiscated and I had been warned that the incident never occurred. A month later, still furious at how I had been humiliated by someone I had learned was a notorious, repeat, offender, I handed in my warrant card. In the years that followed I watched as Driberg manoeuvred, or maybe blackmailed, his way to the top of British politics, was elected chairman of the Labour Party, and was ennobled as Baron Bradwell of Bradwell juxta Mare shortly before his death in 1976. This was my first bad experience in the Met, and it was to prove a lasting one. It reflected not only on Driberg, not only on the willingness of another MP to conspire with him, but the Met’s institutionalised collusion. Curiously, if there was a victim of this all-too-frequent encounter in a public convenience, I felt it had been me.

Many of the other ex-officers opted for police service overseas with Commonwealth forces, and I also went for an interview at the Colonial Office, but although I passed the scrutiny with flying colours, I failed the medical because of an injury to my legs I had sustained while in the army. With that avenue closed to me I accepted a post in the City, working for Rickards, an import-export company in Watling Street.

My experience of the City of London was almost as disappointing as mine in the police. Whereas small backhanders and bribes were the norm in the Met, with sergeants accepting £5 notes to look the other way when a minor charge was dropped, I soon learned that my managing director routinely inflated invoices and issued false receipts in much the same way that the company buyer demanded £500 to place a large purchase. Despite this disagreeable atmosphere I survived for a year, but when the promised company car failed to materialise I jumped ship, and joined another venture, Lamson Paragon Business Systems, which more suited my limited business talents.

LPBS was a pioneer in the new field of electronic automation and computerisation, and I was selected to spend a year mastering this new management tool that promised to transform the way business was conducted. Some of my training was undertaken abroad, and my specialist area of expertise turned out to be retail entertainment, and soon I was cultivating my designated territory, the owners of West End night clubs, in the hope of persuading them to invest in electronic systems that would enable them to exercise greater control in a trade notorious for ‘stock shrinkage’ and the mishandling of cash. I undertook surveys of the needs of the prospective clients, designed a suitable system for them and then supervised its installation. My task at LPBS was to promote the use of automated tills and other equipment that allowed them to keep track of where their money was going and monitor the performance of their managers and transactions, and in doing so I found myself working mainly in the evenings and at night. However, at the weekends I usually stayed with my parents in Hampshire, and it was on one of these occasions that I met June Price, a nursing sister working at the nearby Farnborough Hospital. After a long courtship I found myself under pressure from my father to marry her as our first child, Nicholas, was on the way. Over the following three years that our marriage survived Lisette and Joanna followed quickly. June’s family were landowners in Shropshire, with a large estate outside Shrewsbury, so there was plenty of support for June when we decided to part, perhaps victims of a City of London life that really suited neither of us, or maybe because I was the wrong husband. It was only after we had married that I had discovered she had been engaged previously to no less than three doctors at the hospital, and had something of a reputation for wanting to find a husband.

Inevitably, as a young man with a flat in Hampstead and instant access to London’s most popular nightspots where I could expect plenty of hospitality and entertainment, I was to discover much about the seamier side of Soho, including the fact that almost all my clients had developed a corrupt relationship with the Clubs Office, the C Division uniformed branch unit at West End Central Police Station in Saville Row, responsible for licensing the many private clubs in the area. Quite simply, the clubs needed to operate without police interference, and the best way to guarantee cooperation was to pay off the police in much the same way that some of the East End gangs extorted protection money from the pubs and snooker halls. Regular weekly payments to the appointed bagman ensured no late night raids, no harassment of customers and no official objections when the liquor license was renewed by the City of Westminster magistrates in Marlborough Street. It was during this period, while I was courting my future wife, that I became friendly with Gilbert Kelland, the head of the Clubs Office, who was later to be appointed Assistant Commissioner, Crime (ACC), and established his reputation by investigating and arresting the Scotland Yard detectives who had developed a relationship with a criminal named Naccacio and some of Soho’s most notorious pornographers. I also came to know the Club Office bagman, a young detective sergeant, John Smith, who much later was to be promoted Deputy Commissioner and receive knighthood.

Perhaps surprisingly, in view of what I had learned in the West End, I decided in 1959 to rejoin the police, whose minor corruption seemed tame compared to what I had witnessed among businessmen and traders in the City. I needed a regular income and as a newly married husband and an expectant father the Met offered security, and I found myself posted to P Division in Beckenham where I was assigned a pleasant police flat overlooking the golf course. Soon I was accepted by the CID and was offered a transfer to the Special Branch at the Yard and to royal protection duties, but I preferred honest coppering in the suburbs. Later I was posted to Z Division in Croydon, and then to M Division in Camberwell with a promotion to the rank of detective sergeant. By now I was a single, disciplined, effective plain-clothes man with a reputation of getting results. I had also passed my sergeant’s exam without any artificial assistance, although I knew that it was perfectly possible, especially if you were ‘on the square’, of sailing through the papers if you had the right contacts. The Met set only two promotion exams, and the papers for both could be obtained in advance through friends or the lodge, and this state of affairs had been in existence for years. It was part of the culture, and the justification was that some people worked so hard they needed some help, and that no harm was done because there was a merit element in the competitive nature of the results. Only the top examinees achieved their promotions, but it did no harm to have influential sponsors. In my case I had the benefit of advice from Commander Flood, who had explained how every ambitious police officer needed a career strategy and good contacts. I had been adopted by a mentor, Sam Goddard, who had been a detective superintendent at Catford and, I suspected, wanted to match me up with his daughter, then a law student. He had been part of Lord Trenchard’s ill-fated, fast-track scheme to introduce an officer corps into the Met, and when his grade had been abolished he had languished in his rank for many years, which had given him a particular perspective on the police greasy pole. He was the first of many to warn me that while there were plenty of colleagues willing to back you while you were perceived to be on the way up, the very same people would stab you in the back if they thought you had become a loser. He was a wise man. Always old school, Goddard had urged me to cultivate potentially useful contacts, keeping in touch with anyone who might later become a source, and I possessed plenty of those through my experience in the City. I renewed friendships I had made at Bow Street, and re-established contact with some of the club and casino operators I had met while working for Lampson Paragon. Everyone knows that it is ‘not what you know, but who you know’ and, as the lawyers say, ‘you do not have to read every book, you only have to know where to look’.

While working in Camberwell I gained a reasonable reputation as an active thief-taker, and I was awaiting a further posting, to C8, the Flying Squad at New Scotland Yard when, on Saturday 29 November 1969 The Times printed a front-page article by Gary Lloyd and Julian D’Arcy Mounter, and an editorial written by the editor, William Rees-Mogg, headlined ‘London Policemen in Bribe Allegations. Tapes Reveal Planted Evidence’ identifying me as one of a group of supposedly corrupt CID officers who had been entrapped by undercover journalists. The newspaper asserted that the other detectives had been taking money in exchange for dropping charges, for being lenient with evidence in court, and for ‘allowing a criminal to work unhindered’. I was identified by name as having admitted on tape to having accepted £150 from a criminal, who was protected by the pseudonym ‘Michael Smith’ and two Yard officers, DI Bernard Robson and Gordon Harris, were said to have received more than £400 in one month from the same man. This one newspaper story, about which I had received no warning, was to influence the rest of my life. Overnight, my life as an ambitious CID officer who was going places, was lost forever, and I would be marked out as a man who had brought shame and embarrassment to an elite force. My world simply crumbled, and instead of making decisions and taking the initiative, I was to go onto the defensive, almost permanently.

I had spent years dealing with the underworld, nicking professional criminals and making good arrests, but overnight I had been accused, judged and condemned. I had been a rising star in an organisation that, thanks to numerous television series, enjoyed one of the best public relations images in the world, but now everything had been turned upside-down. I had made hundreds of good arrests, my evidence had helped convict many criminals and I had received several commendations, but all this had been achieved courtesy of the corrupt firm running London’s CID. To some, the more positive my achievements, the worse their implications.

If the background to The Times’ story was even remotely true, it was obvious the evidence to back the allegations had been obtained illegally, and would have been rejected in any CID office which doubtless would have used it as a basis for a further investigation. While The Times may not have been a down-market tabloid, it had no God-given right to ignore the rules of criminal evidence, and in professional terms this was an unprecedented, very public execution.

The result of this bombshell was my immediate suspension from duty while Commander Roy Yorke ordered an enquiry to be conducted by Detective Chief Superintendent Freddie Lambert. Upon reflection, having recovered from the initial shock, I thought I had little to fear from Lambert’s investigation, but as he was preparing his final report in May 1970, which I had learned was set to clear me of all the allegations, he was taken off the case by Yorke’s replacement, Wallace Virgo. This was a devastating blow as I had absolutely no confidence in Virgo, who was himself later convicted of corruption, and not much more in his close associates the two Ernies, Bond and Millen, and his reputation within the Met was that he had developed too close a relationship with Lord Thomson, the Canadian-born proprietor of The Times. This extraordinarily improbable friendship had started when Virgo had been appointed to investigate the Belfast Telegraph scandal, a case in which Roy Thomson, who had inherited a barony from his father in 1951, had been accused of using improper methods to gain control of Northern Ireland’s principal regional newspaper. Virgo had begun by calling for a copy of Thomson’s RCMP file from Canada, and using that background as justification for a telephone intercept warrant which enabled the lines at his home in Kensington Palace Gardens and his business in Long Acre to be recorded by ‘Tinkerbell’, the Yard’s secret intercept facility in Ebury Bridge Road. Then, as now, such taps cannot be used as evidence in any criminal trial, but the leads they offer can prove invaluable, and this was what had happened with Thomson who had built his expanding business empire by taking control of investment trusts through offers of future lucrative directorships to compliant trustees. This had been his ruthless methodology in Canada where rumours were rife of his approaches to influential shareholders so he could take over nearly fifty provincial newspapers. The precise details of what happened over the Belfast Telegraph, which was owned by a trust where the beneficiary was rumoured to be a five year-old child, are locked away in the High Court where there had been furious litigation in the Court of Protection, but in the end Virgo had cleared Thomson of any misconduct, who had gone on to take control of The Times, then a failing but prestigious title in financial trouble. With Wally Virgo in charge of the decision to accept or reject the claims of a pair of young Times journalists, both still in their twenties, who had only been on the paper for four years, I knew the likely outcome, and my worst fears were realised.

In the West End it was clearly understood that Commander Virgo had carved up the vice scene and licensed all three major players, Bernie Silver, James Humphreys and Jeff Phillips. All had led long criminal careers, but counted senior police officers among their closest friends, dining with them regularly, attending the same Lodge meetings and even going on holiday together. Humphreys’ own criminal record dated back to the end of the war when, aged fifteen, he was convicted of house-breaking and theft of a car, and sent to an Approved School. Since then he had served two prison sentences, for receiving and for theft, and in March 1958 had been described by a judge as ‘a hardened and dangerous criminal’. Upon his release from Dartmoor he had opened his first club, in Old Compton Street, and asserted that he had started to pay off his local CID officer, DS Harry Challoner, who was later to be tried for planting bricks on demonstrators protesting against a visit to London in July 1963 by King Paul and Queen Frederika of Greece, and be declared insane.

By chance I had myself encountered Harry Challoner, because the mental hospital to which he had been sent was Cane Hill, a large establishment on our manor. We were under instructions to drop in on him from time to time to see he was all right, but I never thought there was anything wrong with him. Known as ‘Tanky’, Challenor had served with the Commandos and the SAS during the war, and had been decorated with the Military Medal while operating far behind enemy lines in Nazi-occupied France. At his trial at the Old Bailey in June 1964 the jury had taken less than a minute to declare that he was unfit to plead, but found three other young detectives guilty of perverting the course of justice. Two received four years, and the youngest received three years, but Challenor spent just two years at the Netherne Hospital, in Surrey, and Leavesden. Upon his release he went on a tour of the battlefields in Italy where he had fought during the war, found a job with a firm of solicitors in Norbury and in 1990 wrote his memoirs. According to the Masonic gossip in the Met, Challonor had been given the benefit of advice from Edward Clarke QC, a future Old Bailey judge and leading member of the Sir Edward Clarke Lodge, to which Challenor happened to belong. Whenever Clarke defended police officers, it was noticeable that their pocketbooks always went missing and were unavailable for inspection, which is precisely what happened to Challenor and his subordinates.

The point about Challenor was that he represented my most prolonged contact with a supposedly corrupt officer, and he had achieved considerable notoriety because his case was the first real proof of a problem within the CID, or at least within West End Central.

Challenor had been in a different league to Virgo and his immediate subordinate Bill Moody, and his offence, of planting evidence on a demonstrator, was quite different to taking money off criminals like Humphreys, but I knew that the Met had found a breakdown through overwork a convenient explanation for the lack of any forensic evidence in the suspect’s clothes to support Challoner’s claim that he had found a brick in his pocket. In the aftermath of the demonstrator’s acquittal at Bow Street, on a complete lack of any forensic evidence to show any brick had been anywhere near the defendant’s clothing, Challenor was prosecuted, and an enquiry had been set up by the Home Secretary , conducted by Arthur Evan James QC, at which several of the detective’s earlier arrests had proclaimed their innocence, but in fact only five convictions were quashed as unsafe, and all allegations of assault and taking bribes were rejected.

Challenor’s conviction was a milestone and served to undermine public confidence in the police. It also confirmed rumours, that had circulated for years, that the Met did not quite live up to its reputation. Fortunately Challenor was an eccentric, colourful figure who could easily be portrayed as a war hero who had succumbed to the strain of massive overwork, and had suffered a breakdown. In other words, Challenor had been a one-off, and no wider conclusions could be drawn for an unfortunate lapse. Some of us suspected there was rather more to what had been happening in Soho, the patch covered by West End Central in Savile Row.

Humphreys and his wife Rusty ran the strip clubs in Soho while his rival, Bernie Silver, organised the prostitutes and maintained a string of dirty book shops, and Phillips distributed blue movies. Bill Moody had joined the OPS in 1965, and when he had been appointed its head in February 1969 he had institutionalised the arrangement and extorted protection money from all the key players. Regular, weekly retainers were paid, together with an annual Christmas bonus and a lump sum of £1,000 for each new site opened. Managers that made their contributions were never raided; those that fell behind in their payments had their stock confiscated, which was then ‘recycled’ back into the trade. Humphreys, Phillips and Silver were not only free to expand their vice empires, but were even considered suitable guests for the Flying Squad’s annual dinner, as was another colourful character known as ‘Ron the dustbin’.

The allegations of corruption published by The Times could be traced back to Eddie Brennan, a retired safe-cracker who had graduated into fencing stolen property. Brennan was a highly successful criminal who had the advantage of a partnership with a corrupt locksmith who supplied him with duplicate keys to dozens of commercial premises. Brennan chose the targets and then allocated them to one of several London gangs, leaving the professionals to undertake the robberies in return for the privilege of buying the proceeds at remarkably low prices, thus allowing him a very substantial margin. As Brennan’s fame spread, the Yard heard that he was personally responsible for a veritable crime wave that had swept the capital, and in November 1967 a special operation, code-named COATHANGER was prepared by a team of detectives led by Chief Inspector Irvine of No. 6 Regional Crime Squad. The codename COATHANGER was chosen because much of the crime under investigation concerned stolen clothing, and Detective Inspector Bernie Robson from the Yard’s C9 Department took over operational command in October 1969 when the gangs resumed their activities. Of the eleven detectives working on COATHANGER, only two were from the Met, and the rest had been drawn from provincial forces. Robson personally had arrested twenty-two of the robbers, including the technician responsible for making the duplicate keys, but some of these had been copied and circulated, allowing several other gangs to participate in the raids. In fact, so many keys were being passed around that it was rumoured different gangs had turned up at the same premises to rob them at the same time! On one occasion a gang had arrived just as another was coming out, having left nothing worth stealing.

Robson’s first task was to recruit an informant and his chosen target was a professional named Michael Perry, a twenty-two year-old car dealer with eighteen convictions. Perry lived in Nunhead Lane, Peckham and was generally known to be at the very heart of the ‘skeleton key gang’, and when the two men met early in October 1969 Perry had been found in possession of a case of stolen whisky, and had been charged with dishonestly handling. Under pressure, he had admitted knowing the names of ten members of the gang, and five receivers. He was Robson’s best chance of bringing COATHANGER to a successful conclusion, but five days later he was talking to The Times.

CID officers have many ways of cultivating informants but when time is a luxury there are methods of cutting corners and applying pressure. Sometime called recruitment by ‘the hard way’, the objective is to coerce cooperation through old-fashioned intimidation. In Perry’s case he fell for an old expedient, and he was simply tricked into touching some gelignite which was immediately sealed into an evidence exhibit bag, thus leaving him open to the charge that his fingerprints had been found on a piece of explosive recovered from a crime scene. Once the fingerprint identification had been confirmed, and usually accepted by juries as irrefutable scientific evidence from a forensics expert, the target would be facing a long prison sentence unless he agreed to become a CID ‘snout’. In Perry’s case, he was threatened with eight years inside unless he identified London’s master fence and his key-man, and he confided his predicament to Brennan who offered the story to The Times. However, the version peddled by Brennan omitted the true background to COATHANGER and centred on the allegation that a young man had been the victim of a scheme run by two Yard detectives who had planted evidence on him and then threatened to charge him with possession unless they were paid a large sum of cash. This rather sanitised tale of extortion was accepted without question by the newspaper which assigned two journalists to collaborate with Perry who, under their direction, began calling local CID officers with the offer of information.

Perry was suspected as the leader of a gang of young criminals known, after the television series, as ‘the likely lads’ who exploited a contact in a locksmith business. They would drive up to the midlands, visit sometimes several clothing stores in one evening, and empty them, using duplicate keys and wearing white coats to allay suspicion and avoid leaving forensic evidence. Over the past two years they had raided more than a hundred shops, had left no clues, and had stolen more than a million pounds of property. They never forced an entry, and the single common denominator to their crime spree was the complete absence of any usable forensic evidence such as fingerprints, hair or fibres. However, we had heard from informants of Perry’s involvement, but had not been able to prove anything because the likely lads, shrewdly, had been working off our patch. We knew they were all driving around in big cars with pockets full of cash, but we had not spotted them in an actual robbery. We kept them under observation for weeks, and when we had identified most of the gang members we sent a report to the Yard which circulated their details to some of the forces in the midlands that had been plagued by the well-planned and executed raids. For our part, we continued the surveillance in the hope of catching them at home after one of their escapades.

The catalyst was a robbery on 22 September 1969 at the Nuneaton & Atherstone Co-op Society in which a large consignment of cigarettes were stolen, and two days later the Warwickshire detectives descended on Peckham to arrest Perry, and we received a request for assistance which implied that they thought these hardened young south London career criminals would crack at the first sight of a search warrant and an interrogation. The midlands officers wanted our cooperation in arresting all the suspects simultaneously, but the DI at Peckham knew that such tactics would waste six weeks of our time. His solution was to send the visitors to Camberwell with the suggestion that they apply for a search warrant from a local Justice of the Peace who was always willing to sign anything we put in front of him, irrespective of the supporting evidence. As I was later to discover, this particular exercise had proved very profitable for the detectives involved, as the raid resulted in the recovery of a large quantity of cigarettes, only a proportion of which ended up in the property store as evidence. Such diversions were quite routine, but this rather minor episode was to come back to haunt all concerned.

In spite of the successful raid, the visitors really had no evidence against the likely lads, only a strong suspicion, but we were to humour them. Even the Yard, which had put the likely lads under surveillance in the hope of catching them unloading their gear at their receivers, had failed in their task, but all this promised to change when we received a call from Perry offering information.

My first encounter with Perry occurred following his call to our office. Although we had not met previously, I had known his mother, a convicted shoplifter from Woolwich and it was through this link that he picked me as a suitable target. Always willing to recruit a new source, and being under no pressure to achieve any particular results because I was unconnected with the Yard’s COATHANGER operation, I met Perry and made the standard ‘soft’ pitch, that his cooperation with me would result in a measure of protection for him should he come to the attention of the police. This was an old technique, much favoured by my mentor, Ken Drury who was later to command the Flying Squad, and had built a solid reputation while a DI on the Regional Crime Squad I had served on at St Mary Cray, Orpington. Perry seemed agreeable to the suggestion, but when I called for his file I learned that he had plenty of form, and was even suspected of having broken into the tobacconists directly underneath his own flat, which he shared with a man named Robert Laming. Both men were also under investigation concerning a missing schoolgirl who was found to be living with them. In short, they were really nasty villains, and at a later meeting I was concerned that his reason for calling me to a rendezvous was his claim to me that two detectives had planted evidence on him, and he had named Robson and Harris. I had passed this awkward news on to DI Jim Sylvester at Peckham, whom I knew had served with Robson at Chelsea, and would be able to warn them. Six weeks after my meeting with Perry The Times ran their scoop that DI Robson, his assistant ‘Bomber’ Harris and myself, had been meeting Perry regularly to extort small sums of money from him.

The evidence supporting the allegations, which was delivered to New Scotland Yard at 10pm on the night prior to publication, consisted of a long witness statement from Perry and a tape recording, and this was enough for the C1 Night Duty Officer, Ken Brett, to telephone the Assistant Commissioner (Crime) Peter Brodie at home. He ordered Commander Yorke to start an immediate, overnight investigation to be conducted by Fred Lambert, and his assistant, Sergeant Basil ‘Baz’ Haddrell whom I had known as a fellow officer at St Mary Cray, ready for a top-level meeting early on Saturday morning. Lambert had been on call that evening, but was in a potentially awkward position because he had served with Harris at Brixton and later had worked together on the Flying Squad, and had got to know his family. I later learned that Lambert informed Yorke that he had also served with Robson, but Yorke had merely replied that he had also known both Robson and Harris. Lambert was ‘to get on with it and do a good job’, but he was unhappy with his assignment, which was to last six months.

Within an hour of these events I was telephoned at home to let me know what had happened, and as I had worked on several disciplinary enquiries I knew the precautions that had to be taken. I had played a very peripheral role in the Richardson ‘Torture Gang’ case, which had put away London’s most dangerous gangsters since the Kray brothers, and that enquiry had led to ninety allegations of corruption against the officers who had built the prosecution’s case. I had not been one of the team that had investigated Richardson’s lucrative rackets, which including running the car parks at London Airport, but coincidentally I had known Eddie Richardson years earlier when we had both spent Saturday nights at dances held at the Streatham ice rink. Like hundreds of other CID officers, I had taken a few witness statements and followed up some local enquiries concerning the Richardson enquiry, but truly my contribution had been negligible.

Almost immediately after my initial warning I received a call from a Daily Express journalist who read me an extract from the first edition of the next morning’s Times, and I had to suppress a gasp and pretend this was all in a day’s work, while declining to comment. The headline alone made my heart race: ‘LONDON POLICEMEN IN BRIBE ALLEGATIONS. TAPES REVEAL PLANTED EVIDENCE’.

Disturbing evidence of bribery and corruption among certain London detectives was handed by The Times to Scotland Yard last night. We have, we believe, proved that at least three detectives are taking large sums of money in exchange for dropping charges, for being lenient with evidence offered in court. And for allowing a criminal to work unhindered. Our investigations into these men convince us that their cases are not isolated. The total haul of this detective Sergeant John Symonds of Camberwell, and two others, Detective Inspector Bernard Robson of Scotland Yard’s C (Division and Detective Sergeant Gordon Harris, a Regional Crime Squad officer on detachment from Brighton to Scotland Yard, was more than £400 in the past month from one man alone.

I told the Express journalist I had no comment to make, and quickly jumped in my car to pick a copy of the first edition from an all-night newspaper stand in Fleet Street. I skimmed through several paragraphs about Robson and Harris until I reached what were claimed to be extracts of conversations between me and a small-time professional criminal whom I had supposedly met in south London pub car parks. These meetings had been photographed and tape-recorded, and apparently I had advised him: “Don’t forget always to let me know straight away if you need anything because I know people everywhere, because I am in a little firm in a firm, alright?”

In the cold light of day, and taken out of context, the conversation, mixed with every kind of expletive, sounded ghastly, but that is the way you talked to such people. Furthermore, if you were an energetic thief-taker, you would have to endure allegations of that kind as an occupational hazard. That, of course, did not mean that such claims were not investigated to the fullest possible extent, so first I contacted my family solicitor to alert him, and then I searched my own house from top to bottom for any incriminating evidence, such as chemically impregnated banknotes that might have been planted on me, before driving to my office at Camberwell to check my desk. Accompanied by the station sergeant I also went through the prisoners’ property store and examined all the valuables in the safe to make certain that everything logged under my name was properly accounted for. I had heard of so many examples of officers being ‘fitted up’ with compromising evidence that I wanted to be absolutely certain that I was not about to fall into the same trap. My final precaution was to take the key from behind my desk and visit a small locked broom cupboard in an outbuilding that was marked ‘cleaners’ but contained the CID’s secret cache of fit-up exhibits. This was a collection of knives, guns, drugs and masks that were occasionally deployed when a reluctant informant needed some persuasion. In my experience they were the essential tools of the CID officer’s trade, but their discovery during an official investigation would cause nothing but trouble so I carried the lot to my car and drove them to Peckham police station where a colleague willingly accepted them. Finally I took my car to a late night garage and put it on the ramp to examine the underside of the vehicle. Once again, this was a necessary precaution because I had heard of small, magnetised containers packed with banknotes being concealed beneath the engine block. Only when I had completed the most detailed search inside and outside the car did I feel entirely confident about facing Lambert’s investigation which doubtless would begin early the following morning.

It may sound odd that I should have gone to such lengths if I was truly innocent of taking money from Michael Perry, but I had good reason to be anxious. I reckoned that no newspaper would publish such allegations unless there was a verifiable paper-trail, and in this case an absolutely essential component would have been a stash of dirty money. I knew that none existed, but it would not take much effort to find a way of planting some on me, my car, in my desk, or even in my garden shed. By checking all the obvious hiding places, any subsequent discovery would have had to have been based on a plant made after the newspaper had hit the streets, and I would be in the clear.

For a newspaper to behave in this way was, in those days, really quite extraordinary, and for the upmarket Times to indulge in such tactics was unprecedented. Why had the newspaper not taken Perry’s allegations straight to the Commissioner, Sir John Waldron, who was universally respected? Whatever his loyalty to the force, Waldron would had been ruthless in his pursuit of corruption. Even more inexplicable was the newspaper’s willingness to collude with a professional criminal and print a story which, by its nature, presumed guilt. In these uncharted waters I knew that I was in deep trouble. The Met employed 3,250 detectives, but it was my name in the headlines.

On the next morning I went in to my office as usual and awaited my fate, but as I read the front page of The Times again, and read allegations against a total of fifteen colleagues in south London my alarm grew. I had been lumped together with Robson and Harris, and I found it extraordinarily reckless that they had apparently continued to meet Perry after I had warned them. However, one call to DI Sylvester at Peckham established that he had not said anything to Robson, but had conveyed a message to Harris, who later denied he had ever received it. Suddenly Ken Drury’s famous ‘soft’ recruitment pitch looked rather less impressive as it appeared in transcript form in the newspaper’s impassive print, and I realised I would be bound to be tied in with Robson and Harris. As I waited for the inevitable I carefully went through my paperwork, comparing the entries in the CID duty book with my own diary and pocketbook and, after attending a prearranged meeting with another informant unconnected with COATHANGER, finally went home and called in sick to give me some extra time to consider my increasingly precarious position.

By the following morning the situation had changed markedly, and Victor Lissack arrived early, having been despatched from the Yard, with a request that I issue libel proceedings in the High Court instantly so as to prevent any further revelations in The Times. A writ had been drawn up by a prominent lawyer, the ex-MP Edward Gardiner QC, and this was served later the same day, just as I learned that there were some major problems with the Times’ story. To my relief I heard that there was no reference to any money in the transcript of my conversation with Perry, and there was considerable doubt about the ‘continuity of handling’ in respect of the tapes which had been left around on desks at the The Times, played at office parties and even taken home by journalists, thereby mixing up the originals with the copies. Worse, it emerged that the journalists had given money to Perry to hand to the police, which smelt of entrapment, but had failed to take the obvious precaution of searching Perry properly after his meeting to see if he had kept the cash. Combined with the illegal use of a wireless transmitter to record the detectives’ conversation remotely and the illegal recordings of telephone conversations from Perry’s mother’s flat, the case seemed to boil down to the allegations made in Perry’s uncorroborated witness statement. Certainly he had been equipped with a small Grundig tape-recorder as a back-up, but he also had the ability to switch it on and off, which he had done. Furthermore, apart from Peter Jay, the Economics Correspondent, Brennan had been the only other person involved in the episode, apparently employed as a consultant, because the newspaper was unwilling to take any advice from the ex-police officer who worked as The Times’s chief of security for fear of a leak back to the Yard. In short, Perry’s evidence looked very dubious and when a check was made with the Bank of England on the serial numbers of the banknotes allegedly handed to me in October, it turned out that they had not printed nor placed in circulation until six weeks later. This was an important point because The Times journalists insisted they had looked in Perry’s pockets to establish that he had not kept the £50 himself but, crucially, they had failed to search his car. I knew I had not taken the notes, so the obvious answer was that Perry had hidden them somewhere in his car, but they had not thought to search that too.

It was on Lissack’s advice that I made a fateful decision, to immediately start work on a lengthy statement, what I would later call my dossier, in which I detailed the kind of practices required for an efficient CID office to obtain convictions, and named some, but by no means all, of the detectives who cut corners. This was an exercise in self-preservation, and my instructions to Lissack was to keep it in his safe and not show it to anyone unless something happened to me. This was to be my insurance policy, or so I had thought, but I had put my trust in the wrong man.

Lambert’s preliminary report on The Times’ allegations was delivered to the Commissioner on Monday,1 December 1969, and on the following Thursday the Yard announced that Robson, Harris and myself were suspended from duty. It seemed that the tapes were far from conclusive evidence of anything, except perhaps some unwise and colourful remarks made by me. I was told later that when colleagues had listened to the tapes they had laughed because over the years they had all heard the same thing. As I had learned at Ken Drury’s knee, there is a method to gaining the confidence of a professional criminal, and part of the technique is to assure him that you are ‘alright’, and that he will be too if he works with you, to mutual benefit. The crook has to believe that he can have a little license to do his bits and pieces where he can be protected, in return for information and bodies. Whether a detective ever really gives the promised measure of protection is an entirely different matter, but it is accepted that he is going to try and acquire the protection without compromising anyone else, while you are intent on gaining the information without delivering on the rest of the bargain. It is a game that has gone on for years, and all the tapes showed was the extent to which I had learned my trade, and the number of times one could insert swearwords into a conversation. They were not to be listened to by the faint-hearted, nor the middle classes over their breakfasts, nor gentlemen in the clubs in St James’s, but they did reflect life in south London’s criminal fraternity.

Another potential source of embarrassment was a disparaging comment about provincial police officers, and I knew such comments would not endear me to any ‘old swede’ brought in to conduct an investigation of my case. The Met culturally had always been fairly contemptuous of country coppers and in one of the taped conversations with Perry I had gone through the usual routine of building up my own status as a man of influence within the CID, describing myself as ‘a firm within a firm’, using the jargon Perry would understand, so he would know that I was not a person to be manipulated or messed about. I wanted results from him and plain language was called for, although I erred when I slipped into an explanation of how I would not be able to exercise any influence outside the Met. Naturally, such observations, though reflecting the opinions of colleagues, would be bound to irritate provincial officers. I suppose it could also be said that the tapes were an embarrassment to the Yard because, if played at a trial and combined with my explanation, it would show that the Met routinely conned the criminal classes into becoming informants. Somehow this was not a message the Yard wanted to broadcast, or the public wanted to be told. However, even if our conversation might have been a little strong for some tastes, the tapes showed nothing that was directly incriminating, and far from betraying the sound of notes rustling, there was not even a single word recorded about any money, and definitely no threats. With the pay-off notes discredited, and doubt cast on the ‘iffy’ tapes, and nothing awkward in the recording, I really thought I was off the hook, and rightly so.

The impending litigation quickly eliminated further stories in The Times, and the cases against the other twelve suspended officers soon collapsed, leaving a few relatively minor disciplinary matters, and Robson, Harris and me to face the music. However, as the Lambert enquiry progressed, his focus turned on The Times and there was talk of charges being brought in respect of Perry’s deployment as an agent provocateur. This was excellent news, but it did not last long as the Home Secretary, James Callaghan MP, announced that he was to order an outside force to conduct a further investigation. This brought angry protests from the Commissioner, Sir John Waldron, who insisted that Callaghan had no power to interfere with his force which enjoyed autonomy under the Metropolitan Police Act, and when the ineffectual Frank Williamson, then HM Inspector of Constabulary (Crime) and formerly the Chief Constable of Cumbria, was appointed to advise on the matter, helped by a team drawn from the Midlands, the new enquiry ran into the sand, unable to interview any officers from the Met. The conclusion was that Lambert submitted his report, clearing me, and recommending that I be allowed to return to duty. As for Williamson, he retired prematurely at the end of December 1971 and never received the knighthood that is usually granted to HM Inspectors. Within the Met the view was that Williamson, with his austere Plymouth Brethren background and crusading zeal, had been entirely the wrong man for the job. He could see no reason for any police officer to socialise with criminals, whereas it had long been accepted in the CID that the only way to catch thieves was to go for an occasional drink with them. It was a fundamental difference in attitude, and one that broke Williamson, or at least earned him the contempt of the Met which understood what needed to be done to fight crime effectively.

Before he left Williamson did get a couple of scalps, but the case were absurdly trivial. Two uniformed constables at Peckham, Paul Watson and David Lovett, were tried at the Old Bailey for having claimed to have arrested Michael Perry in September 1969 on suspicion of having stolen a van. In fact four other officers had made the arrest, but in those days it was routine in a straightforward case for a nominee to take the case to court, especially when a guilty plea was likely. However, in Perry’s case, which went to trial in May 1970, it emerged during cross-examination that Watson and Lovett had not been the officers who had taken Perry into custody, so they were themselves arrested. The judge, Mr Justice Neil McKinnon, gave them a conditional discharge and recommended the two men, who had excellent records and were described as ‘absolutely dedicated’ to the job, should be allowed to stay on the force, but a disciplinary tribunal held a few days later required them to resign, a sure sign of the new climate in the Met.

This, however, was not the end of the matter, for in May 1970 Lambert was suddenly removed from the enquiry by Virgo, told to take early retirement on medical grounds and replaced by DCS Alfred ‘Bill’ Moody, whom I had known as a sergeant at Croydon. I would have described myself as an acquaintance rather than a friend, and the only social events we met at were connected with boxing, for we were both ‘pugs’, which tended to blur the disparity in our ranks. I had been the light heavyweight champion of all three services, and Moody had won the Met’s middleweight title.